Written by Lusanda

25 Jun 2021

This blog is inspired by Jordan’s Real Talk series on Instagram, where we tackle difficult topics frankly, to give you tangible insight into the ups and downs of living in Sweden. Heads up: This will be a long blog on a touchy subject, but it will still be only a brief summary of a complex and subjective issue. Some sections will discuss violence and discrimination and may be difficult for some readers.

This article was written during the COVID-19 pandemic and may not be up to date. COVID-19 restrictions are no longer in place in Sweden.

So is there racism in Sweden? It depends on who you ask and what your understanding of racism is.

Some people might think of overt racism such as neo-Nazis, extreme right-wing views, genocide, or explicit violence. Some people think that racism is a thing of the past. This is only one side of a very bumpy coin, and the absence of extreme forms of racism like this does not mean that racism does not exist in other subtler, more deep-rooted forms. You might remember the worldwide flood of outrage, protests, and discussions from the Black Lives Matter protests last year following George Floyd’s murder and you might have come across concepts like institutional and systemic racism, cognitive biases, and microaggressions. While these forms of covert racism are not always obvious, they are far more common than we’d like to believe – and because they are also difficult to pinpoint and have everyone agree that’s what is happening, they are also more difficult to uproot and dismantle.

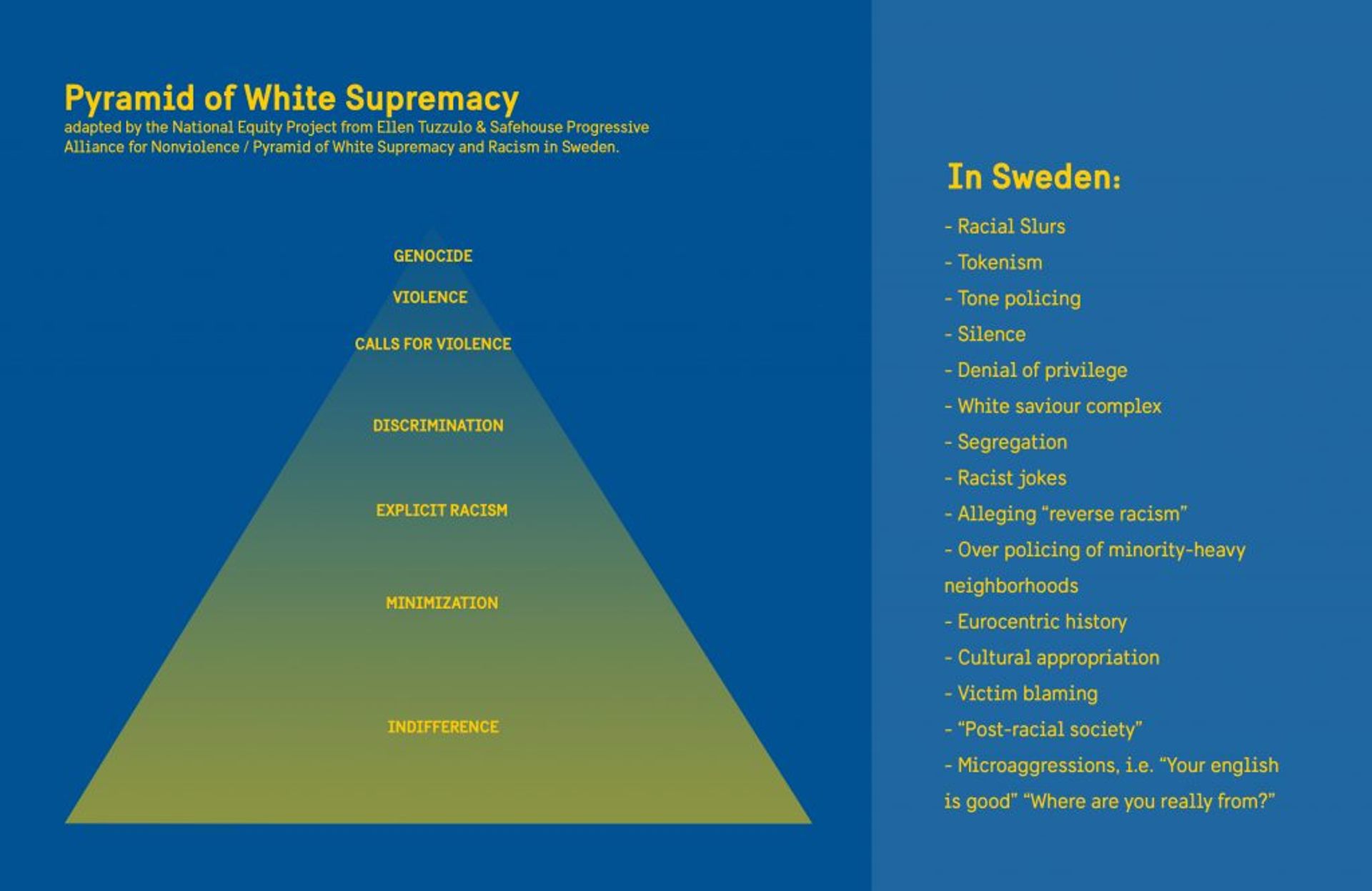

Racism happens at many different levels

You can think of racism as a structure like a pyramid and the bricks at the bottom are subtle and less violent but uphold the entire structure that allows more violent acts to exist. The higher up the pyramid you go, the more violent and extreme. The most violent cases happen less often but silence and indifference are quite common and happen every day. The pyramid of White Supremacy below illustrates the many layers of discrimination that occur at the individual, state, or societal level and on the right, you can see some examples that specifically apply to Sweden.

- Genocide

- Violence

- Calls for Violence

- Discrimination

- Explicit Racism

- Minimization

- Indifference

In Sweden in particular, what is most common that we identified as Evolving Higher Education is:

- Racial slurs

- Tokenism

- Tone Policing

- Silence

- Denial of Privilege

- White savior complex

- Segregation

- Racist jokes

- Alleging “reverse racism”

- Over policing of minority-heavy neighborhoods

- Eurocentric history

- Cultural appropriation

- Victim blaming

- “Post-racial society”

- Microaggresions, i.e. “Your English is good” or “Where are you really from?

Which mostly exists within Indifference and Minimization, with less common instances Explicit Racism, Discrimination, and Violence.

What is my understanding of racism?

If you ask me? My perspective has been shaped by my experience as a black woman from South Africa. My understanding of racism is also influenced by South Africa’s history, the legacy of apartheid, and the ongoing fight for racial equality that lives and breathes throughout our culture to this day. I’ve had to learn, understand, and confront racism from a young age so I understand my views may differ from anyone with a different (or even similar) background. I had very high hopes for Sweden as a so-called post-racial society and I might have been idealistic. While I haven’t experienced any outright violent discrimination (it seems to happen very rarely, in general) I have definitely experienced covert racism through microaggressions, racist jokes, tone policing, and the denial, indifference, or minimising of racial discrimination. In conversations with my friends and classmates from other countries, cultures, and races, I’ve found that if they have experienced racism and discrimination, it’s most often subtle and covert. From this view, racism does exist in Sweden. So I believe that racism includes all attitudes, policies, and actions that maintain racial inequality, whether covert or overt, deliberate or unintentional. Although, I’m certain that my perspective might not be shared by other BIPOC who have had a different experience in Sweden↗️.

A large benefit of studying in Sweden is being exposed to various cultures because you find many international students from all over the world. You learn so many different perspectives, which encourages empathy for people and cultures you haven’t encountered before. This benefit of course has its own downsides – different cultures experience different conflicts, oppressions and privileges, and many people are ignorant to some issues if they haven’t had to deal with them in their home countries. You can imagine, this can cause some conflict, and I’ve certainly gotten into arguments with people who make offensive remarks that are hidden as “innocent jokes”, or who actively hold beliefs that are ignorant at best and bigoted at worst.

But Sweden is “Not Racist”

Racism is a global problem, and as such, Sweden is not a utopia free from that either. Of course, there are places in the world with more violent and deliberate structures of inequality and coming from South Africa, I’ve seen, experienced, and heard of some horrible instances of racism. That said, the general response doesn’t tend to shy away from racism because its such an obvious issue – at least compared with how I’ve seen it handled in Sweden. My biggest struggle in adjusting to Swedish culture was the denial or very passive dismissal that what I was seeing, and feeling was actually happening. You’ll find many people in Sweden would say they are “not racist”, but this often comes from that first definition of overt and extreme racism at the top of the pyramid. If I try to engage further on this, people tend to get uncomfortable, shy away and avoid it, or try to quickly change the subject. This can feel confusing when someone otherwise describes themselves as progressive, tolerant, or an ally. There’s a difference between being “not racist” which is a passive defence, rather than being actively anti-racist.

Anti-racism vs “not racist”

- With people merely being “not racist”, the vulnerable remain vulnerable structrally and institutionally

- Anti-racism is devoted to long-lasting change

- It is focused on fixing the problem not masking the disease

- Recognizing the privilege for such a problem to matter in ones day-to-day life

- Not being overtly racist can disguise covert racism

How do I mentally prepare for this?

So how do you prepare for this as a new student? If you’re BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour) this might already be familiar to you and you might have already googled “Is Sweden racist?” as a precaution – like I did. Unfortunately, I didn’t find as much helpful information about this to help me mentally prepare for this experience. I found plenty of information about dressing for the weather, preparing for winter depression, stocking up on Vitamin D, and the Swedish concept of lagom, or “just enough” – the culture of moderation that filters through food, social etiquette, and creating a healthy work-life balance. But very little about racism, anti-racism work, or how Sweden’s culture of neutrality means most people prefer to avoid conflict, or sometimes are in denial that racism exists.

On the other hand, you might have never encountered such issues before and this might be shocking or not make any sense to you. I also understand that it’s a very uncomfortable topic, and people can respond defensively if they feel like they are being accused of being racist or perpetuating racist ideas and practices. If you’re met with these feelings, I urge you to listen first. Try to sit with those feelings of discomfort and be open-minded to learn. There are plenty of resources to read, watch, listen, and share; created to educate everyone on racism and inequality. You may be tempted to reach out to your BIPOC friends and classmates for help to understand, but this might be a tricky approach. I can’t speak for all black people – let alone all BIPOC – but I know I personally don’t have the energy to educate every single person I encounter, every single day, in every single conversation about something that can cause conflict and discomfort, especially if I’m often one of few people in the space who are BIPOC in Sweden. Not every BIPOC is comfortable to engage with this, so be careful and considerate in how you approach these conversations. If you establish trust with someone first, and try not to centre yourself in these discussions, you might find a connection that will be more meaningful than trying to get someone else to do the emotional work for you.

Experiences of Refugee Integration

Text source: University of Gothenburg’s Centre on Global Migration (CGU)

You might have heard about anti-immigrant sentiments spreading in Sweden before, and this is another complex issue that is partly related to racism. Anti-immigration views and policies are often based on fear and viewing immigrants as a threat to Swedish society and culture and I’ve often heard casual criticisms of immigrants that veil ignorance or prejudice. Many people blame immigrants for taking away jobs, misusing welfare systems, damaging Swedish community and nationality or the deterioration of public education and healthcare systems. Immigrants are also more highly suspected to be criminals and get blamed for isolating themselves from Swedish communities and culture. These prejudices are even worse for immigrants of colour, so racism and antiimmigration intersect. These assumptions aren’t fair, and based on myths which have been proven to be false by Government.se article on facts about migration, integration and crime in Sweden ↗️. It’s also unfair because it places heavy blame on outsiders and shifts focus away from the structures that make it difficult for immigrants to integrate into Swedish society. It generally is difficult to settle in and make close friendships in Sweden because it takes a very long time, and it’s typical within Swedish culture for people to keep to themselves and be moderate in approaching other people – which is also typical among Swedes to other Swedes, by the way!

According to University of Gothenburg’s Centre on Global Migration (CGU), while most European countries are multicultural, with people from many different cultural backgrounds, languages, ethnicities and religions, integration policies since the 1990s have shifted away from celebration of these differences, and instead towards assimilation or civic integration. Still, segregation and social marginalisation is quite typical in multicultural European cities. At an institutional level, since the 1990s, multiple laws have changed that made it tougher for immigrants to secure a residence permit and/or citizenship; particularly for immigrants outside of the European Union. Other strict rules have been introduced such as bans on veils and hijabs in schools. It’s a complex issue but is often framed in an oversimplified way by politicians and the media. Immigration is hotly debated in Swedish politics and often anti-immigrant narratives are strategies used by opposing parties to gain votes and following among the public. This also increased following the refugee crisis in 2015, where Sweden accommodated a large number or refugees and immigrants into their welfare system within a short time period.

On average it takes six to ten years for immigrants to successfully establish themselves in the Swedish labour market.

The focus on evidence of integration is also often numbers-based but misses some nuances – for example politicians might report the number of immigrants who are formally employed as evidence that immigrants are successfully integrating, but they don’t often consider the quality of the work available isn’t sufficient for individuals to have successful careers on the same level as native Swedes, particularly where immigrants are regarded as inferior workers to native-born Swedes. It also doesn’t take into account the cognitive bias that employers might have, which favours candidates who are fluent in Swedish and have a similar background and established network, and misses the potential of qualified candidates with a different background who would require some support from their employer to be better trained and integrated in the work environment. On average it takes six to ten years for immigrants to successfully establish themselves in the Swedish labour market. This is quite a paradox, because Sweden is considered a world-leader in their work on integration and tends to rank highly as responsive and well supported financially. There are many strengths to the current system and the quality of life for everyone on Sweden is generally great, but it’s not perfect and there are cracks in the system that contribute to growing inequality within Sweden. Refugees and immigrants are still vulnerable to relative poverty, unemployment, and poorer health and socioeconomic factors have impacted COVID-19 incidences, with immigrants at higher confirmed cases and deaths.

What is Structural Inequality?

- It’s when the structures that exist within society both embody and practice inequality that prevents certain groups of people from succeeding within that space.

- It can happen within the family, religious organisations, educational organisations, places of work, sports, the arts, social media, or any established structure in society.

- The most common forms of inequality you find in larger society work (sometimes inadvertently) against people of colour, women, LGBT+ groups, and other minorities such as Latinxs in the US, and people of Indian origin in South Africa.

The tough pill to swallow

Sweden is largely tolerant and progressive and can feel welcoming to outsiders. This is how I’ve felt throughout my stay in Sweden so I was reluctant to acknowledge that some of the uncomfortable experiences I had were microaggressions based on my race. For example, people may mean well and think they are complimenting me when they say, “Wow, I can’t believe you speak English so well” or “Why do you speak English so fluently?” But their tone is surprised or condescending and hinting that they assumed differently because of my race. This doesn’t mean every single comment is racist; I can recognise the difference between someone who is asking out of fascination with my race because that’s the most important thing they see about me compared to someone who is genuinely curious and wants to connect with me because they are interested in me as a human being. These differences are usually subtle and make it hard to express why it makes me feel uncomfortable. Some people might believe that BIPOC are too sensitive and that we’re going out of our way to make things an issue of race but contrary to that, it’s actually very uncomfortable and scary to talk about it if you can’t trust that the person you’re confronting will listen and try to understand or help you.

I’ve learned from experience that it’s sometimes easier to try to diffuse tension and avoid conflict – so sometimes I’ll laugh it off or change the subject. This isn’t entirely helpful though and I often wish in those scenarios that I had allies who could notice what was going on and call it out when I’m too scared to. I’ve always felt relieved when someone supports me so I don’t look like the overly demonised stereotype of “the angry black woman”. When I’ve spoken up and engaged in an argument and I’m alone on a group of people who don’t care or try to dismiss my experiences, it feels alienating, and I’ll often think back to the incident for days or weeks on end, convinced that there must be something wrong with me – especially when people gaslight me into thinking I’m imagining things or that there’s no such thing as racism in Sweden. Now I know that internalising all these feelings of fear, discomfort and alienation contributed to my depression, and it was a long and slow process to open up and find support for this specific aspect of my life in Sweden.

One of my white counsellors was very reassuring about my struggles with schoolwork, feeling doubtful of myself, and the difficulty of being in a new country during the pandemic. However, when I started talking about my experiences of racism, they couldn’t understand at all. The microaggressions didn’t make sense to them and I had to tell them about a more explicit experience where a white classmate was screaming the N-word to his friends, clearly making them very uncomfortable, and when I confronted him, he took it lightly and brushed it off. My counsellor responded with shock and said they couldn’t believe this could happen in Sweden. I’m describing this experience because it shows how there’s many people like my counsellor who mean well and are tolerant and supportive, but are still ignorant to the realities of how life in Sweden can be different for outsiders. Sadly, it can get worse. A friend from the Evolving Higher Education group has had someone yell, , “F*** you, N****r” at her in the street from a moving car. Another friend didn’t receive effective care at a doctor’s visit, because he argued her headaches must have been a result of her wearing a hijab. Someone mentioned at an anti-Asian hate online conference that they overheard someone reputable at their workplace say, “It doesn’t matter if all the Chinese people die from COVID; they don’t even have hearts anyway” and most people laughed – and they didn’t lose their job. Last year, a Chinese student and his girlfriend were assaulted in Stockholm for wearing face masks↗️. Their attackers taunted them by using slurs, mocking the Chinese language and asking them where they were from before telling them to “take off the f***ing masks” and eventually physically attacked them. Sadly, this is not an isolated incident, there are other anti-Asian hate crimes that have increased since COVID spread ↗️ and the victims found that many of their Asian friends had also experienced racial abuse.

According to The Local, as of 2018, at least 69% of hate crimes in Sweden are xenophobic or racist, ↗️ with the remaining 12% motivated by sexual/gender orientation, and 19% based on anti-religious motives. While these incidents are horrible and shocking, they are still in the minority in Sweden and don’t reflect a high risk of hate crimes daily↗️ (Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR)) . I feel the safest I have ever felt in my life while living in Sweden and I don’t live in fear of violence but it’s still important to know that while Sweden has come very far from its colonial history, it’s still not perfect↗️.

Support and community

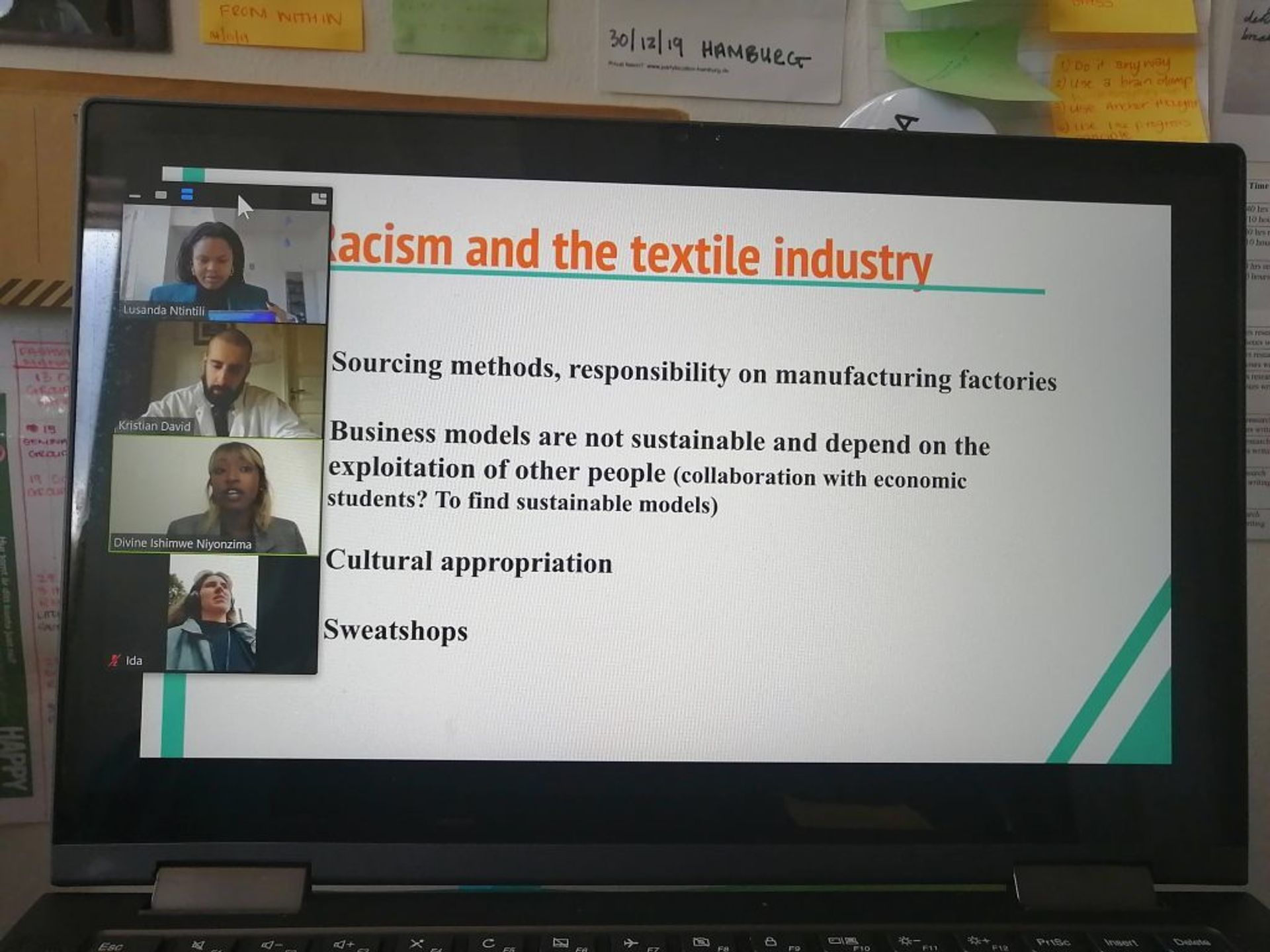

As with everything, with the bad also comes the good. Once I realised what I was feeling wasn’t imaginary and I started speaking up – voicing my frustrations to my friends and counsellors – I became more empowered within my experience. Microaggressions no longer affect me like they did a year ago because I no longer wondered what’s wrong with me, I know that the other person is in the wrong. I’m not angry at all of Sweden either but I’m critical of the individuals and policies that contribute to inequality, while still being able to appreciate the value of my experiences here. It also helped me to find a support network. I joined Evolving Higher Education, a student-founded organisation whose main goal is to ensure that anti-racism education is implemented into all of the programmes at the University of Borås. We shared our stories over fika, shared articles and resources, and we planned petitions, emailed the University staff and eventually presented to the textile faculty board members.

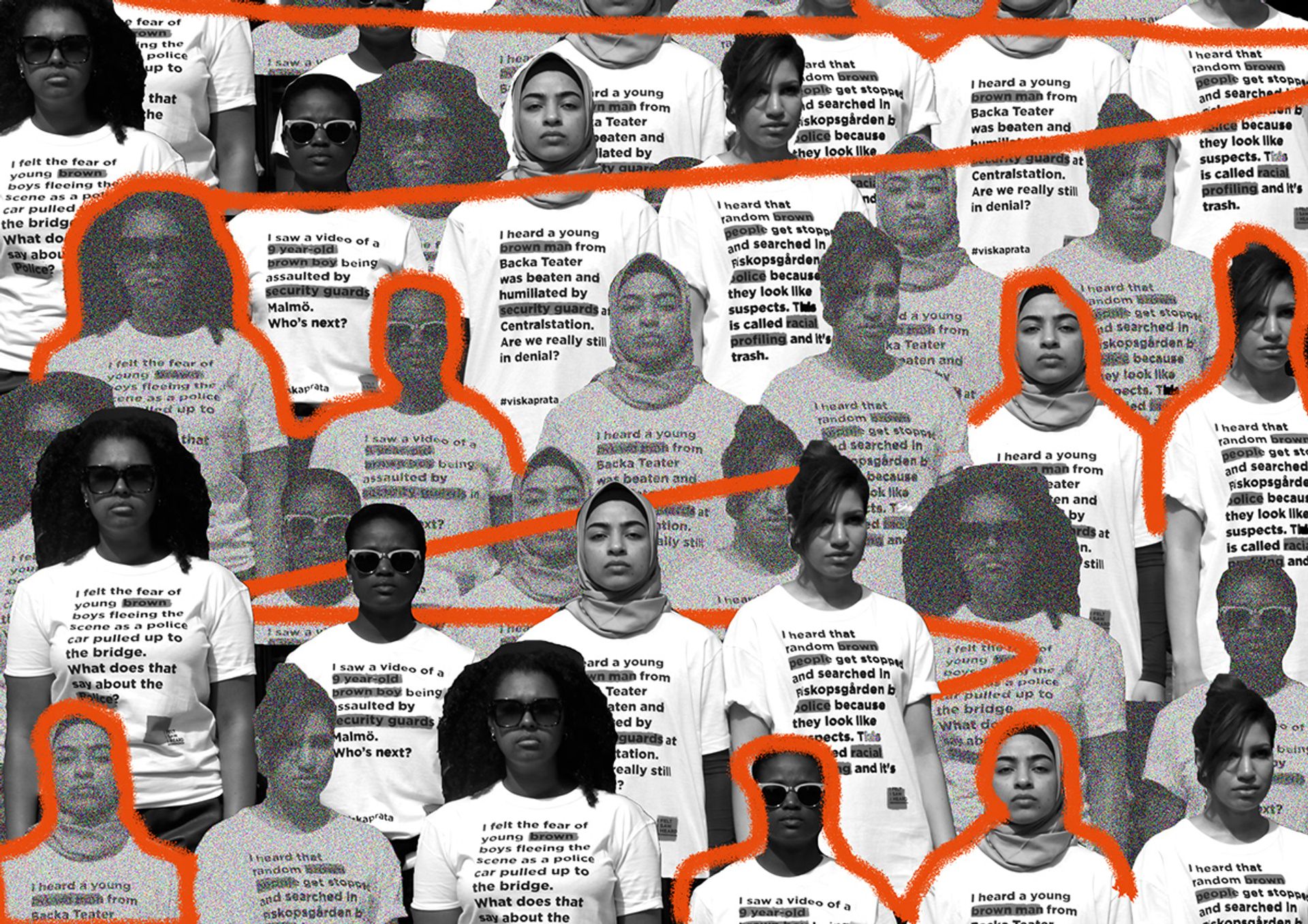

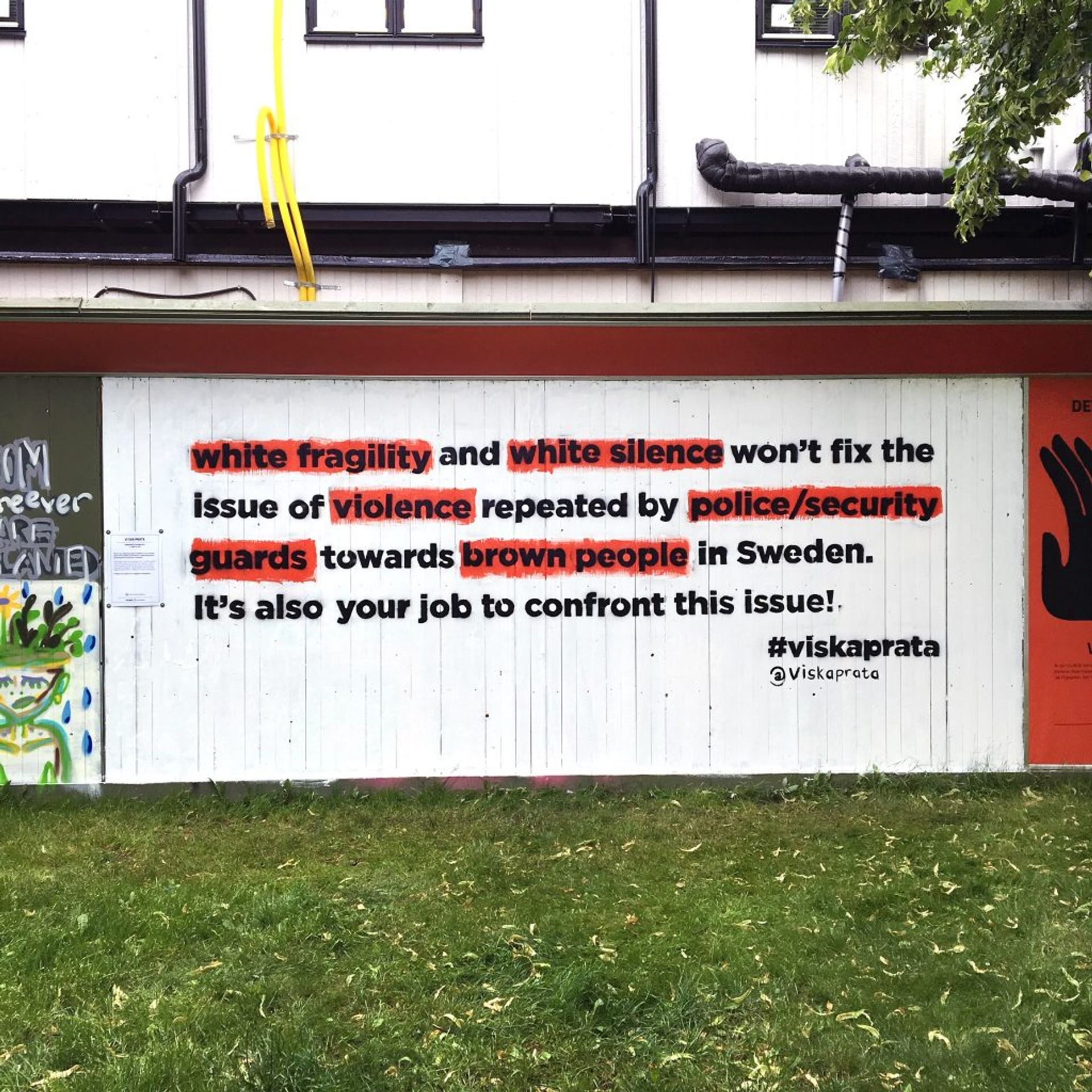

I also found online conferences through Facebook and learned about how Sweden’s colonial legacy shaped the country as it is today, and why Black Lives Matter protests are important here too↗️. I learned about anti-Asian hate and damaging stereotypes in the media, the diversity of Asian identities and experiences and how I can support the cause as an ally – I also confronted my own biases. I also learned about the policy issues that make Integration into Sweden difficult for refugees and immigrants. I spoke with my friend Nontokozo Tshablala who inspired me with her protest art performance called #viskaprata↗️ – the public performance used Tshirts printed with questions to challenge different audiences to confront racism and racial injustice through police/security guard violence and racial profiling withing Gothenburg and othe Swedish cities. The more I engaged with other people, the more I felt like I was part of a community driving change. In my friendships, I’ve also been quite lucky and I’ve attracted friends who are open-minded, and genuinely willing to learn more, challenge themselves and provide empathic support, and to become better allies. They’ve also gone forward to continue our conversations with their network to people that might not be willing to listen to me but are more prepared to listen to what they have to say. I’ve found my little family in Sweden that helps me feel safe, seen, heard, and valued, and I wear my blackness with even more pride today. I encourage you to be kind to yourself and to others, and nourish those connections that keep you safe, but also challenge you to grow.

What is anti-racism education?

- Inclusive and reflective of ALL student experiences

- Understanding privilege by actively working against ignorance in an intersectional manner (This is inclusive of not just race but gender, class, sexuality, disablity, religion, etc.)

- Reframing history to be more accurate and representative, not in a tokenist way

- Rethinking power dynamics

Time to Act

As I said before, much of the work that needs to be done to dismantle racism requires being actively anti-racist. This means more effort to combat racism, self-reflect what you have internalised, revisiting history to be more accurate, speaking up and standing together with allies and marginalised people. This is in no way a full list of steps you can take, but it’s a start – I encourage you to keep researching and engaging in dialogue beyond this blog.

- Speak out against injustices when you see them – even if they are at a dinner party with your problematic uncle who tells way too many casual racist or sexist jokes. Speak out not only when it will make you look good, but even where it’s uncomfortable.

- If you encounter any issues with your teacher or a classmate, please report it to your university. There are protocols against discrimination, and they are obligated to address these issues.

- Follow thought leaders and activist groups that are focused on anti-racism work like Expo, a Swedish anti-racism organisation.

- Research and read more racism and antiracism literature like this comprehensive database from Merced College of Anti-Racism & Equity Resources.

- Start or join a book club to share and keep talking about antiracism literature.

- Find or create antiracism communities through your university – you’re not alone and you’ll find many other students are concerned and don’t know what to do as individuals, but you’re stronger within a community of support.

- Protest – sign petitions, join marches, organise boycotts, spam organisations with emails, the list of actions is endless.

- Share your resources – you never know who you might impact in your network

- Double check arguments and sources – in the age of fake-news, its important to have measured critical thinking on the validity of arguments.

- Look after your mental health – this is not an easy battle and it can take it’s toll, so check in with yourself and your safe spaces.

- Be consistent and patient – its a marathon; not a sprint, so results will often be slow but hopefully much more steady than once-off performative efforts.

Please understand, my goal in writing this blog is not to shock you or discourage you from coming to Sweden. Instead, it’s just the opposite. At Study in Sweden, we aim to provide insight into daily student life and give advice or a hands-on perspective to help prospective students. I believe being transparent (especially about difficult topics) can empower you to have a more realistic outlook on what to expect from the experience. I think if I read a blog like this sooner, it would have helped me realise that I was not wrong to feel discomfort, and instead be brave and bold in using my voice to call out injustices and racism. We should also be bold in the face of this problem, because ignoring it won’t make it go away – it will only make it worse. A fairer and healthier future will require us not to be colourblind, but instead to be colour brave. We can find strength and insight from our differences and embrace them to create richer and more interesting experiences and supportive communities. You have a right to be here, and a right to be yourself. I’m certain you will have in incredible time in Sweden, and learn and grow from the challenges.

Continue the dialogue and make changes happen