Written by Ravindu

12 Oct 2025

Hi There! It’s Ravi, and I’m back again for yet another year of content and blogs! And what better way to kick things off for the new year than by putting you straight into the action here at university?!

It’s been just over a month since I commenced the second year of my bachelor’s program in Bioinformatics at the university of Skövde. And let me tell you, it instantly feels different from the first year. Courses are no longer introductory. They dive deeper into specifics within a subject. On the computer science side, we’re working more with programs for statistical analysis of data. From the biology side, we’re exploring processes that lead to genetically cloned species. Sounds cool, right?

One of the courses I’m currently taking is called Molecular Genetics. The highlight of this course is a full week dedicated entirely to lab work. Sweden is known for being a pioneer in science and technology, especially in the natural sciences, and that’s one of the big reasons why many students come here to study. Naturally, I was curious to see what labs here would be like and how they might differ from the ones I’ve done before.

What is the lab about?

Now let’s get to the cool stuff!

The goal of this lab, simply put, was to take a gene from one species and incorporate it into the DNA of another to see how it’s expressed. The gene we worked with was Luciferase, which comes from fireflies — it’s the one that makes them glow in the dark! We inserted this gene into the DNA of E. coli bacteria, with the hope of getting them to glow too

This is probably one of the most interesting labs I’ve done yet! It’s fun but also thorough and intensive, which seems to be a common theme with courses in Sweden. Most of the time, you feel relaxed and chill, but that doesn’t mean you’re not doing anything demanding.

This also marked the first time I’d be writing a full lab report, an important milestone for any scientist. During the first year, we wrote different sections of lab reports separately, but now it was time to bring everything together and write the full thing for the very first time

Lab partners!

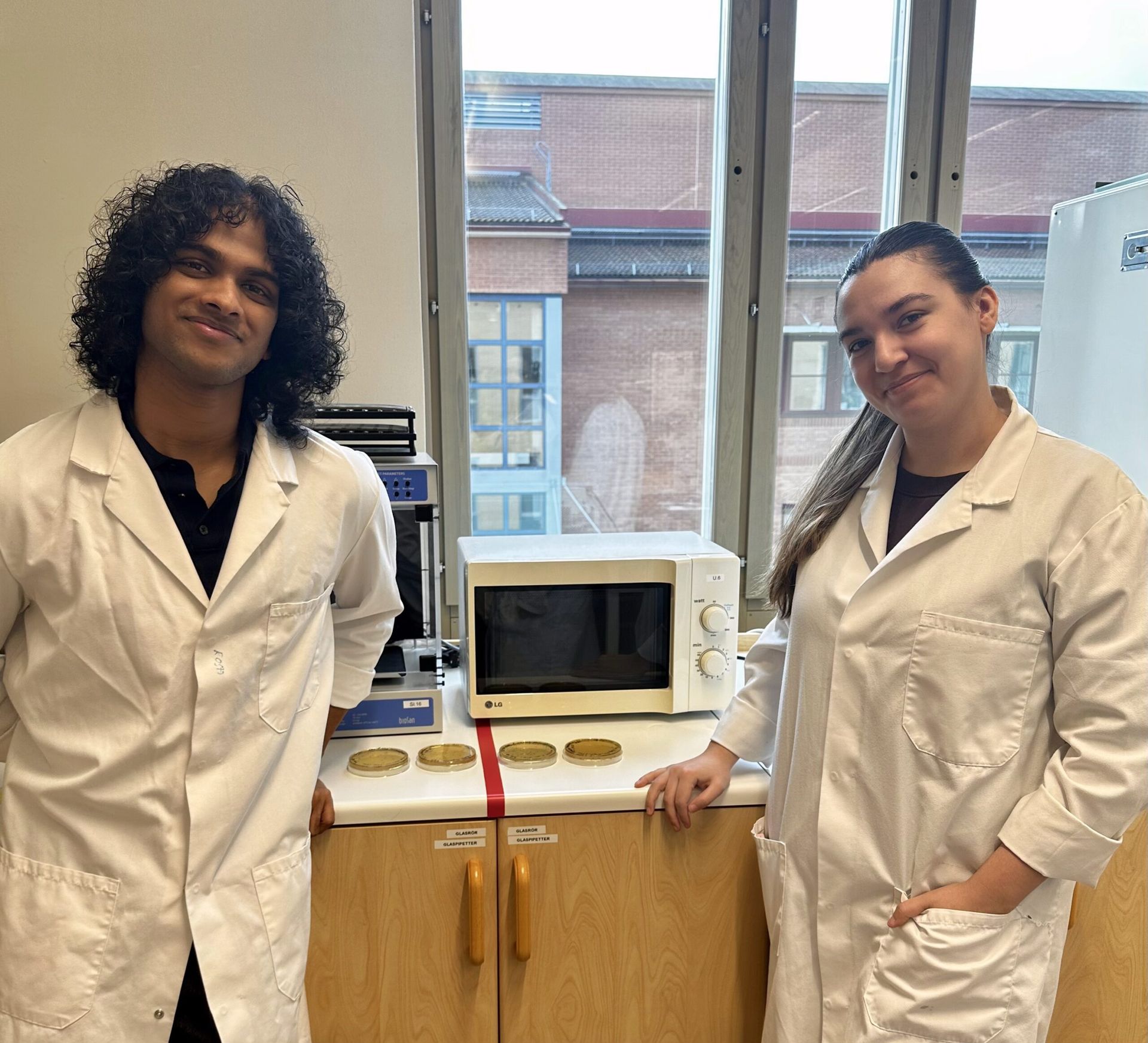

The entire lab and report were done in pairs assigned by our course supervisor. That made many of us nervous at first; we were used to choosing our own lab partners, usually our close friends. Working with someone new felt a bit intimidating, but that’s also what real research is like. In a new lab, you don’t always get to pick your colleagues!

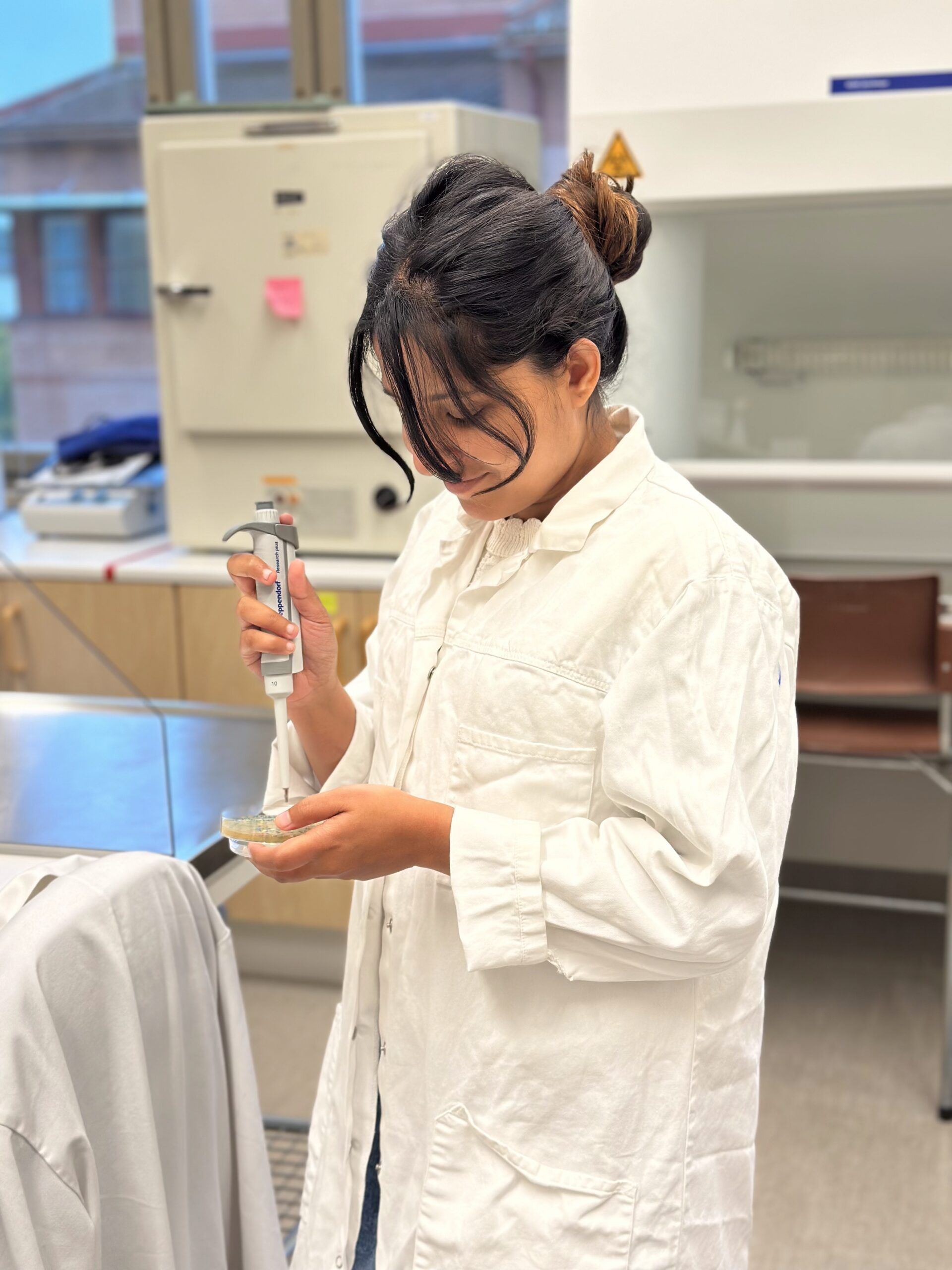

Luckily, I got an amazing lab partner. Everyone, give it up for the wonderful Michelle!

Before the lab week

Even before the lab week began, we had to write a laboratory contract between partners, detailing everything from how we’d communicate and plan our work, to what we’d do if someone got sick or couldn’t attend. It also included how to handle situations if one partner wasn’t contributing responsibly.

It was an interesting exercise. I’d never thought about what it’s like to sign a real agreement before doing lab work. We even had to bring the signed contract on the first day of the lab; otherwise, we couldn’t participate. Yes, it’s that strict!

We were also sent a lecture video explaining the lab, along with the lab manual, to study in advance. There was a quiz(known as a Dugga here in Sweden) that we had to score 100% on to enter the lab. I know — high stakes! But after two attempts, I passed.

Before the official lab week, we also had a prep day, where we prepared the growth media for our bacteria, including selective components like antibiotics so that only the bacteria we wanted would grow. It was a great practice run before the real experiments began.

How did we do it?

Cutting our gene off

The first day was all about cutting up the Luciferase gene from the firefly. Don’t worry — no fireflies were harmed! The gene was already contained in a piece of DNA called a plasmid, which can be purchased from a supplier, so there were no ethical concerns.

We carried out our reactions using genetic scissors called restriction enzymes, and added reagents to help the process run optimally. We also prepared the vector — the piece of DNA that would transfer our gene into the bacterial cells — using the same “scissors” so it would fit perfectly.

Pasting our gene into a transporter

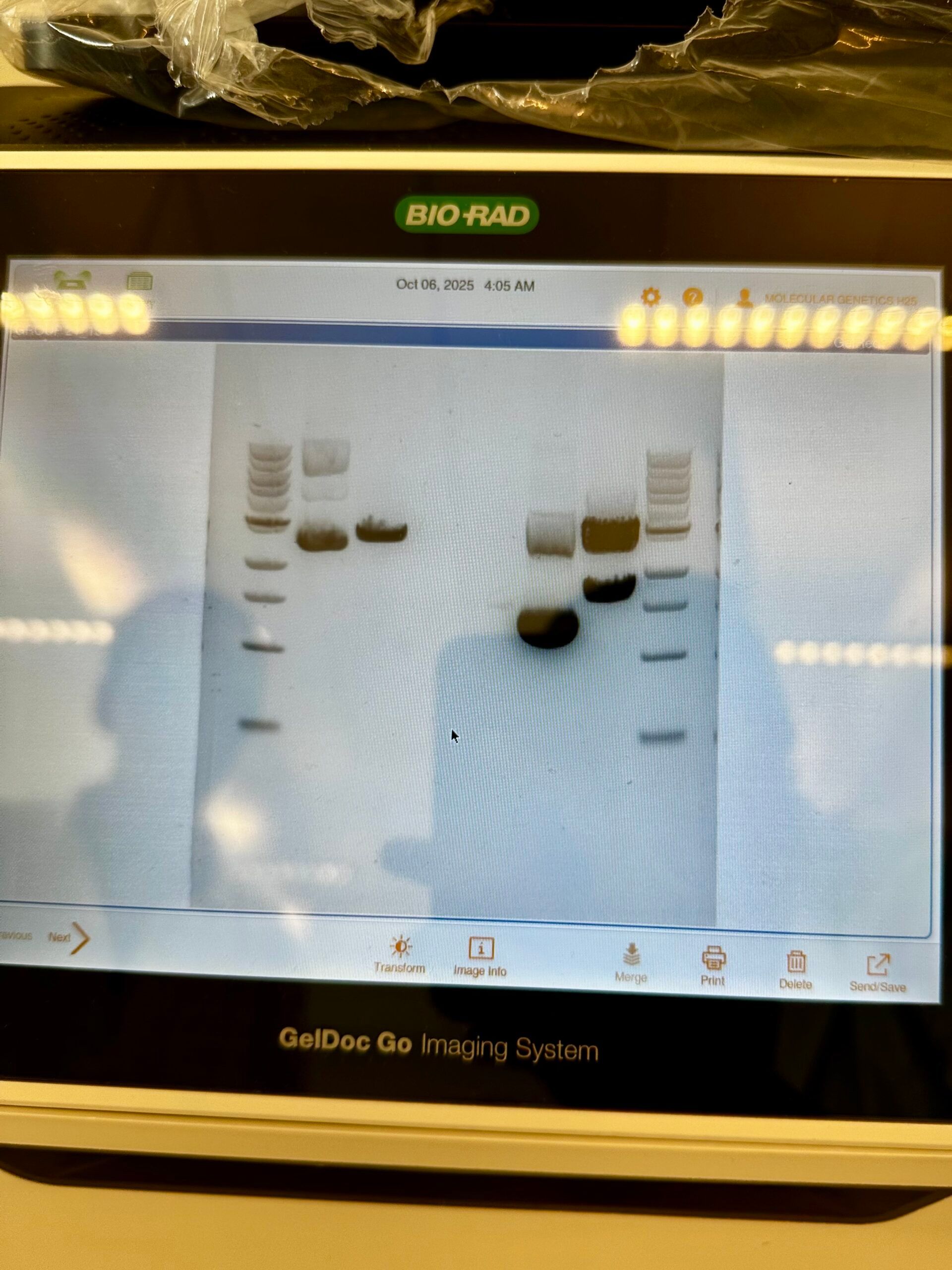

Since DNA is too small to see with the naked eye, we used a process called gel electrophoresis to check whether the fragments we cut were the right size. Once we had the correct pieces, we combined them in a process called ligation, using an enzyme that acts like glue. We left them overnight for the reaction to complete. After leaving them overnight, we had to confirm that the DNA was indeed pasted into the vector properly.

Putting the gene inside the Bacteria

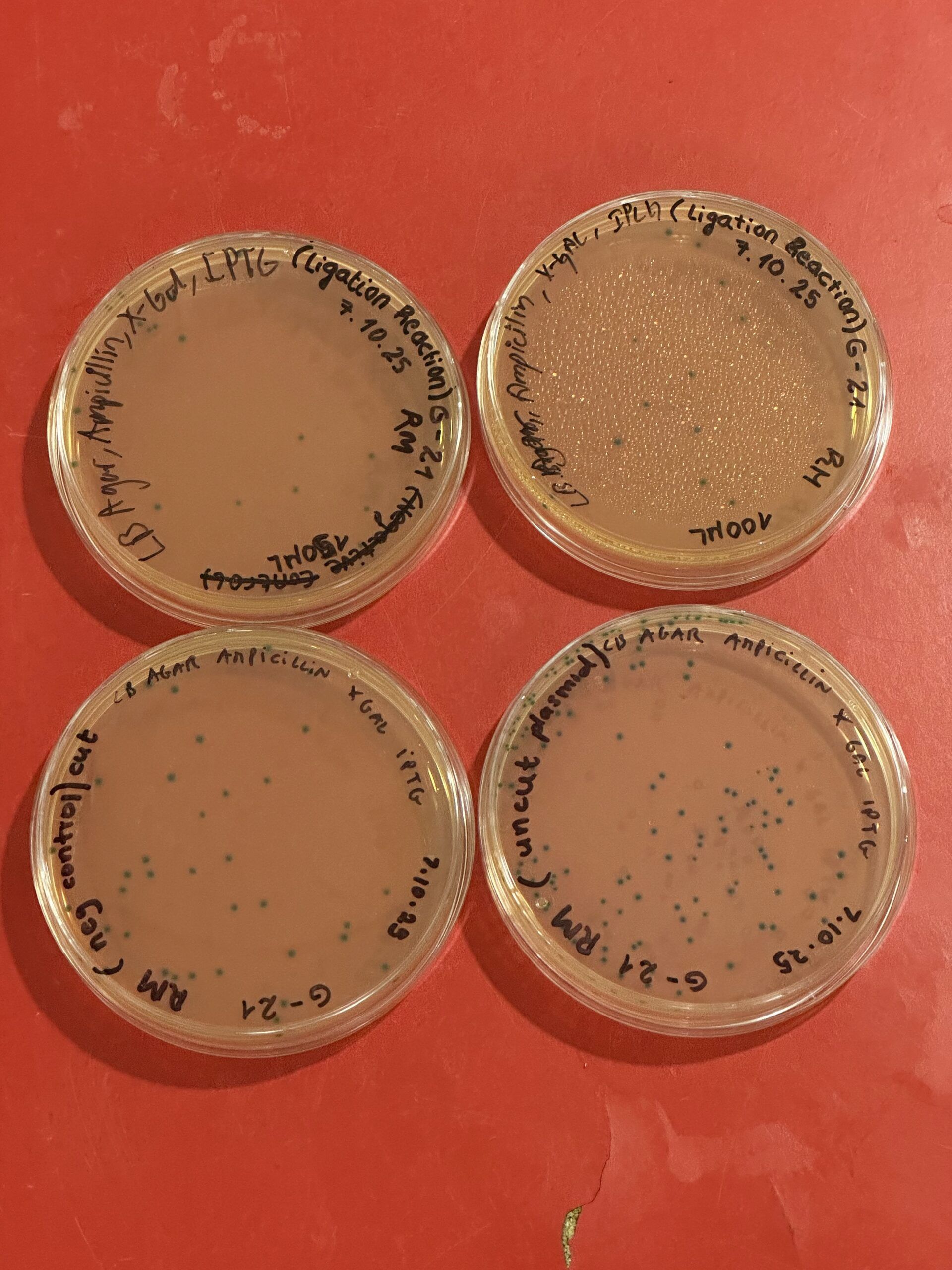

We then introduced them into colonies of our bacteria, E. coli. In order for the bacteria to uptake this new DNA into their cells, we did a small procedure called “Heat Shock” where we manipulate their surrounding temperature by using a water bath, so that they will uptake it. We then plated these new modified bacteria onto growth plats, and let them grow overnight.

The next day, we checked whether we had growth on our plates. One thing to notice is that the plates contained a component called X-gal which allowed us to differentiated bacteria based on whether they have taken our gene. If they had taken up our gene, they would appear as white colonies, and if they hadn’t, they would appear blue in color. Unfortunately for Michelle and I, and also quite a few other groups, we didn’t have white colonies. So we had to take samples from other successful groups to continue our lab.

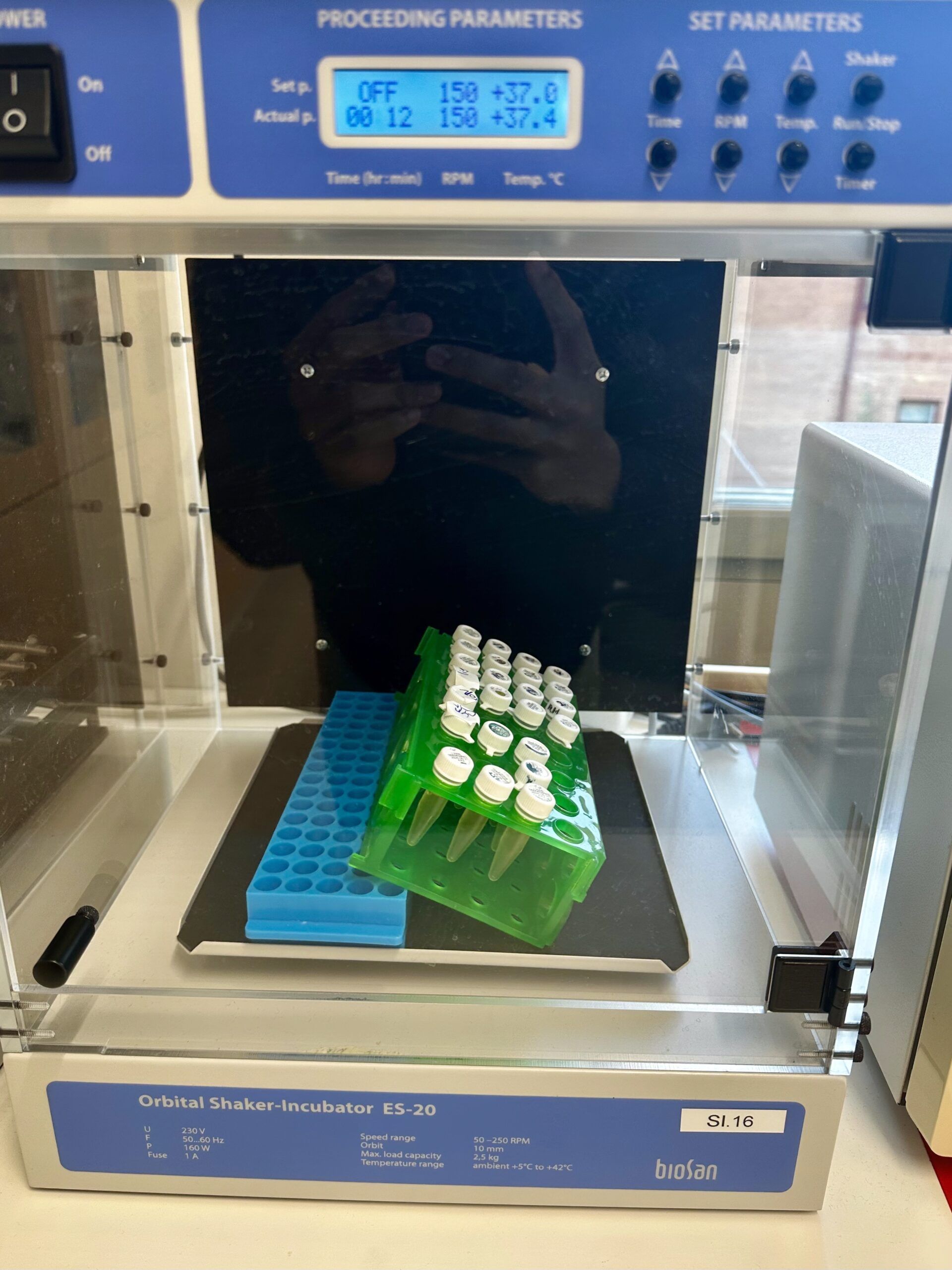

Measuring Growth Rate of the new Bacteria

We then transferred some bacteria into test tubes with growth broth and incubated them under optimal conditions for growth. We had to take readings of how much they’ve grown every hour to plot a growth curve for them. So most of this day was going to the lab for 5 minutes, taking their readings, and then taking a 1-hour break, over and over again. It might not sounds exhausting, but the repetition got to us. By the end of the day, most of us were brain rotted and the lab turned into a sketching session of human portraits. I know, insane!

Seeing If They Actually Glow!

The last and final day was to see if our bacteria has produced the protein from the firefly gene that is responsible for the glowing effect. We carried out some dilutions, prepared samples at different concentrations and then took them to a computerized machine to test for luminescence. Since they only produced the protein in low quantities, we unfortunately can’t see them glowing with our naked eyes, so we have to use a machine.

But after 5 days of work, it was the moment of truth. We inserted our samples into the machine and waited for the results to be displayed on the computer screen. After what felt like eternity (I am exaggerating of course, it was about 20 seconds) the results finally arrived. Our sample of bacteria…. was producing light!

✨ And that’s what a week of labs in Sweden looks like!

A mix of science, teamwork, patience, and fun; and seeing that final result made every long day worth it! What stood out to me the most was how well-equipped and spacious the labs were. We never felt cramped or rushed. Everything was organized so we could focus on actually learning and experimenting. The instruments were top-notch, and the setup made it easy to understand every step of the process.

I love that we learn complex scientific concepts here through experiments that are genuinely fun to do. It’s one thing to study genetics in theory, but it’s another to see glowing bacteria that you made yourself: that’s when science really comes to life!